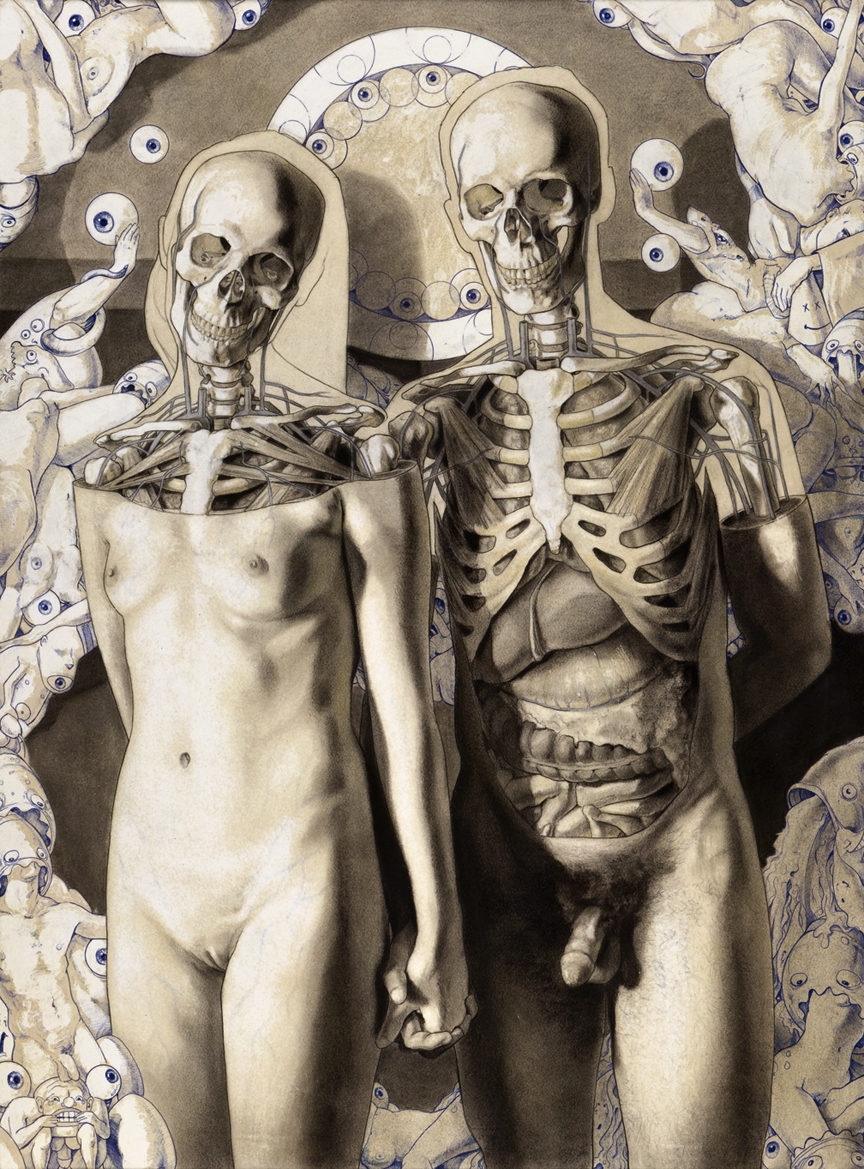

Continuing with the rather morbid theme is another short audio piece based around a hospital mortuary, taken from my ongoing radio project which is probing contemporary attitudes to death.

What's interesting is that mortuaries are notoriously hard to find within hospitals, they're rarely signposted and often kept out of sight from patients and staff. It is almost as if death, through an act of denial, is banished from all walks of hospital life, forcing it underground where it remains out of sight and out of mind.

This is perhaps understandable when we consider the way in which modern medicine deals with death. So often is it concerned with prolonging life and keeping a patient alive that death has come to be seen as 'failure' - the inability to sustain life. As such death represents medicine's limits, it reminds us of our own mortality and as such is buried away within the hospital. This isn't just medicine's fault, it's a product of society and our own collective inability to accept death, we seem to live very much in denial, avoiding the 'd' word at all costs.

As a result those who work in hospital mortuaries take on an almost ghost like or gothic quality, whose activities remain in the shadows and unknown to the majority who dwell in the wards above. So what exactly goes on in a hospital mortuary? What do these places look like and who would we commonly meet in such a place?

It is perhaps only through the heavily stylised perspective of television and film that we gain any sort of insight into such places. Programmes such as CSI and Silent Witness are famous for their representation of pathology and post-mortem procedures, but they depict a world which is somewhat detached from the reality of such work. These programmes are slick, full of drama and entertaining to watch; they do little to challenge our relationship with death and present a very skewed image of those who work with the deceased. Instead they seem to maintain a common perception that death is something quite perverse, that mortuaries are dark gothic places and that pathologists run around solving murders (and of course that all bodies end up in the mortuary because of hideous murders).

Obviously these programmes shouldn't to be re-written to reflect reality (probably wouldn't make for very entertaining viewing), but it's interesting none the less to look at how they deal with death and the contrast between fiction and reality.

So the hospital mortuary remains a place largely unknown and unless you were unfortunate enough to visit one (dead or alive), it's unlikely that you'd ever get a chance to peer inside. I certainly had no idea of what to expect when I recently visited the mortuary at Sunderland Royal Hospital. In the end it was perhaps not surprising to see just how normal mortuary life was, from sitting around drinking tea in a staff room to the usual 'office banter' being thrown about as the day went on. Pathologist Dr Stuart Hamilton was my guide for the day and he very kindly showed me round, you can listen to a brief audio tour below:

[soundcloud width="100%" height="81" params="" url="http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/20493361"]